- Home

- About

- Old Newspaper Articles

- List of Articles

- Herbal Healers

"The Seattle Times" - February 2nd, 1984

By Frederick Case

Then:

"Doc” had the solemn visage of a Manchu emperor and all the reassuring bedside confidence you'd expect of a fourth-generation physician.

The Idaho pioneers who quaffed Dr. C.K. Ah-Fong's mysterious healing herbal potions included the governor and several state senators as well as many "celestials' (as whites then called the Chinese immigrant community).

Ah-Fong also treated miners - and the honky-tonk girls whose favors they brawled for.

The Chinese herbal specialist imported most of his remedial ingredients from China, where he was trained. But some were indigenous products, such as the locally caught reptiles from which he concocted rattlesnake liniment.

Few doctors, white or Chinese saved more lives in the lusty, lead-slinging years of Idaho’s gold-and-silver mining boom. However, until the 1970s, Ah Fong’s name was forgotten as any mountain ghost town. Then white scholars stumbled onto his story.

Few doctors, white or Chinese saved more lives in the lusty, lead-slinging years of Idaho’s gold-and-silver mining boom. However, until the 1970s, Ah Fong’s name was forgotten as any mountain ghost town. Then white scholars stumbled onto his story.

They believe that the role of Chinese medicine in the winning of the West has been gravely underrated. And they feel that Ah-Fong deserves place in Western frontier history as much as celluloid celebrities such as Wyatt Earp, Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill.

Later this month, the Chinese medico’s memorabilia will be displayed at Wing Luke Memorial Museum. 414 Eighth Ave. S. The free exhibit will be shown Feb. 17 to May 1, then will tour other Washington museums for the rest of the year.

The project director is Paul Buell, a University of Washington graduate Sinologist (expert on Chinese History) who also teaches Latin, German and Japanese at Nova Alternative School.

Exhibition designer is Kit Freudenberg. Wing Luke Memorial Museum director.

Buell and Christopher Muench, a medical Anthropologist teaching at the University of California at San Francisco, retrieved Ah Fong’s mementos from a cache of 19th century historical relics stored in the building that used to house the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Buell says their discoveries included a supply of powdered rhino horn, a rare aphrodisiac, valued at $36,000.

Aging photo chronicle Ah-Fong’s American odyssey. One shows him on arrival from China in 1866, a crew-cut Chinese medical-school graduate in his early 20s. Another portrays him at the peak of his career, when he was an elderly member of Boise’s business community, respected for his medical abilities and personal charm.

A measure of Ah-Fong’s skill is that in 1903, when the federal government cracked down on medical quackery, he was granted an American medical degree. Buell believes Ah-Fong may be the only Chinese herbal physician ever granted that distinction.

Even if Ah-Fong helped win the West , Boise (which the Chinese called “Cowrie City”) has no plaques or statures to commemorate him.

But at least one printed record attests to the esteem the city accorded him. When his first wife died in 1902, the Idaho Daily Statesman reported that the funeral procession was the largest in the city’s history, and the cortege included the governor and congressmen.

Respected Ah-Fong’s life was. Dull it was not. Not long after the funeral, the sexagenarian took a new bride, Mabel, age, 18.

But surviving relatives say, around 1908 a young suitor from a rival tong (a Chinese fraternal organization) arrived from Portland to lure Mabel away.

Then Ah-Fong Dispensed a potent remedy.

Just as the fugitives’ train was about to steam out of Boise, it was surrounded by a posse of Ah-Fong’s friends – waving axes.

Mabel changed her mind abruptly and returned to domesticity with Ah-Fong.

Ah-Fong worked until the 1920s, died in 1930 and is buried in China. His descendants continued the business until 1964.

Buell believes there is another key to Ah-Fong’s popularity in Idaho: “Venereal disease was rampant among Idaho miners, and alleviating it was one of Ah-Fong’s specialties,” the scholar says.

Buell, vice president of the Chinese Society of the Northwest, is subsidizing some of the exhibit costs from his own pocket. “The Chinese can be proud of how important their medicine was on the American frontier,” he says.

Now:

The herbal medical art that Dr. C.K. Ah-Fong practiced so well in the pioneering days of Idaho lives on. In fact, it's flourishing only three doors down the street from the Wing Luke memorial Museum, where Ah-Fong's memorabilia will be on exhibit this month.

The herbal medical art that Dr. C.K. Ah-Fong practiced so well in the pioneering days of Idaho lives on. In fact, it's flourishing only three doors down the street from the Wing Luke memorial Museum, where Ah-Fong's memorabilia will be on exhibit this month.

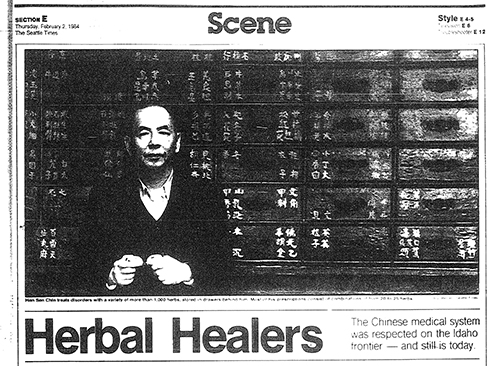

Since 1950, Hen Sen Chin has operated the Hen Sen Chin Herb Co., offering the same kind of authentic Chinese medical care as Ah-Fong did from 1866 until the late 1920s.

Willard Jue, retired director of the University of Washington Herb Garden, says Hen Sen is eminent among the handful of Chinese herb doctors still practicing in Seattle (they include Johannes Liu and Choy Kai-Chiu). Jue calls Hen Sen "a master."

The diplomas on the walls of Hen Sen's little consulting room are from Chinese traditional medical schools in Hong Kong and Taiwan. However, Hen Sen Chin doesn't have an American medical degree, which Ah-Fong was granted.

Also, Hen Sen never touches his patients, whereas Ah-Fong spent a lot of time dressing bullet wounds.

Hen Sen Chin, 61, is a small man with a big smile and penetrating dark eyes. He mixes his English conversation with a sort of background static of Chinese words.

In his cluttered little shop next door to a Chinese family club, Hen Sen ministers to a clientele that includes as many whites as Asians.

As did Ah-Fong, Hen imports his herbs from mainland China, about 9,000 assorted pounds of them a year. He stocks about 1,000 different kinds. Most of his prescriptions contain from 20 to 25 herbs.

The herbalist's sole concession to technology is the color photo he takes of each patient sticking out his tongue.

"Tongue tell me many secrets," he says, in rhythmic voice. He keeps the photo with the patient's case history, referring to it as he ponders which medicines to prescribe.

After 34 years, Hen Sen has written a prescription for himself: retirement, His daughters don't want to take over, so he's training his assistant, Helen Fong, 28, to maintain the venerable tradition.

It's easy to be skeptical of Hen Sen Chin's medical expertise. But it's just as easy to find patients who attest to his remarkable success.

For example, there's Wing Luke Museum Director Kit Freudenberg, who suffered from persistent respiratory and appendix problem. "Just by altering my diet, Hen Sen seems to have cured both ailments," he says.Company: The Hensen Herbs